Why Stories Make You Smarter Than Self-Help Books

I spend a decent amount of time at bookstores, and I’ve noticed something.

The adults browsing the fiction section fall into two distinct camps: college students reaching for Penguin paperbacks, and seventy-year-old professors emeriti in tweed jackets. Meanwhile, the self-help aisle is packed with everyone else, thirty-somethings in business casual leafing through "Atomic Habits" and "The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People."

The distribution is bimodal, and I think I know why.

The young read fiction because they haven't yet learned to be embarrassed by imagination. The genuinely brilliant read fiction because they've looped back around to understanding that pure information transfer is the least interesting thing a book can do. But there's a vast middle ground of people who have just enough education to feel insecure about it, and these folks read non-fiction exclusively. They read because they love being seen learning, more than they love the process of it. I know. I’ve been one of ‘em, at various points in my life.

The dirty secret about non-fiction is that most of it could be a blog post.

These books follow a template: introduce a counterintuitive finding, tell three anecdotes that illustrate it, mention some studies (p < 0.05, naturally), provide a framework with a memorable acronym, conclude with actionable advice. Stretch this to 250 pages, add some graphs, and you have a bestseller. The information density is incredibly low. There are zero complex systems of thought to impart; you're learning to repeat interesting-sounding facts.

Fiction (by contrast) smuggles actual complexity into your brain. When Dostoevsky spends fifty pages letting Raskolnikov justify murder to himself, you're living inside a mind that's trying to reason its way to atrocity. You understand something about human rationalization that no Gladwell volume could teach you. The knowledge comes embedded in context, emotion, and contradiction.

It can't be reduced.

I suspect this is why the smartest people I know tend to quote novels more than they quote non-fiction. They'll reference the Grand Inquisitor or mention something about whales etc, and these literary touchstones carry more meaning than any TED talk summary ever could. The metaphors are load-bearing. They contain compressed wisdom that unfolds differently each time you examine it.

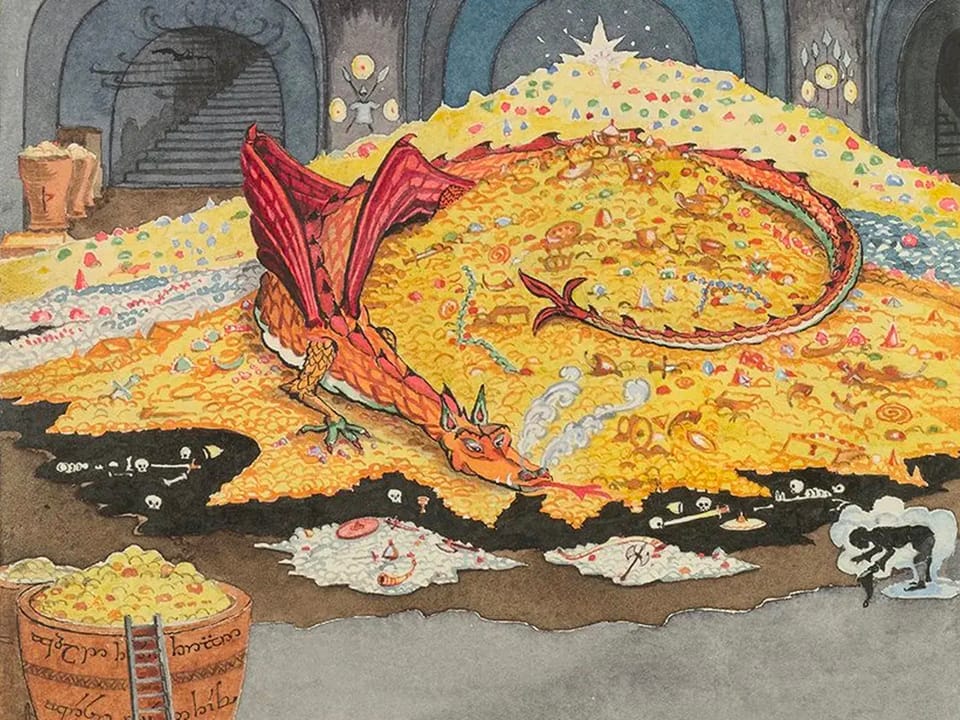

What Tolkien accomplished in "The Lord of the Rings" eclipses any and every non-fiction book ever published about leadership or virtue or the nature of power. Middle-earth presents a complete moral universe where power corrupts absolutely, where the small and humble accomplish what the mighty cannot, where mercy and pity have unexpected consequences. You absorb these lessons through narrative, through watching characters make choices and face their results. The Ring is a better illustration of the corrosive nature of power than anything in The 42 Laws - because it's a metaphor, and metaphors work on you in ways that direct statements can’t // won’t // don’t.

There's a reason every major religion transmits its deepest truths through parables rather than propositions. The various authors of the Bible could have written "Seven Habits of Highly Effective Disciples" but instead, they told stories about seeds and soil, about lost coins and prodigal sons. The Buddha could have published "Mindfulness for Beginners" but instead there are koans and sutras full of contradictory wisdom.

Pure information transfer fails to change people.

Stories work.

The “midwit” trap is thinking that explicit instruction is superior to implicit understanding. Someone reads "How to Win Friends and Influence People" and learns techniques. Someone reads "The Unbearable Lightness of Being" and learns what it feels like to be every person in every kind of relationship, to watch love curdle into resentment, to see how societies constrain and shape individual choices.

Which knowledge is more useful?

Which makes you wise?

I used to think I was being practical by reading mostly non-fiction. I was learning things! Accumulating facts! Becoming informed about psychology, economics, history, science. But the conversations that lingered were with people who read novels. They have a different kind of intelligence, more contextual and subtle. They understand human nature in a way that knowing cold facts about cognitive biases never quite captures.

Self-help books operate under the assumption that wisdom can be systematized and imparted through instruction. But wisdom resists systematization. It's pattern recognition across too many variables to count. It's knowing when rules apply and when they don't. Fiction trains this capacity by forcing you to navigate moral and social complexity without clear answers. There's no "key takeaways" section because life doesn't have key takeaways.

I think about the bookshelf in my office. There are some non-fiction books I'm glad I read once. There are novels I've read five times and will read again. The novels keep yielding new insights because they contain genuine complexity, instead of a cherry-picked selection of simplified models. CS Lewis understood more about courage, friendship, temptation, and sacrifice than the combined authors of every book in the business section. He understood it the way you can only understand something when you build a world from scratch and watch how different souls navigate it.

Maybe students read fiction because they're not yet corrupted by the need to seem informed. Maybe the extremely smart read fiction because they've realized that seeming informed is worthless compared to actual understanding. And maybe the rest of us are stuck in the self-help aisle, hoping that some author has figured out the trick to living that we can learn in twelve chapters.

But Tolkien already told us the trick: the way is shut, and you have to walk it yourself.

(No amount of non-fiction can walk it for you.)