Why Cringe Tolerance Separates Builders from Non-Builders

Perfectionism Kills Potential

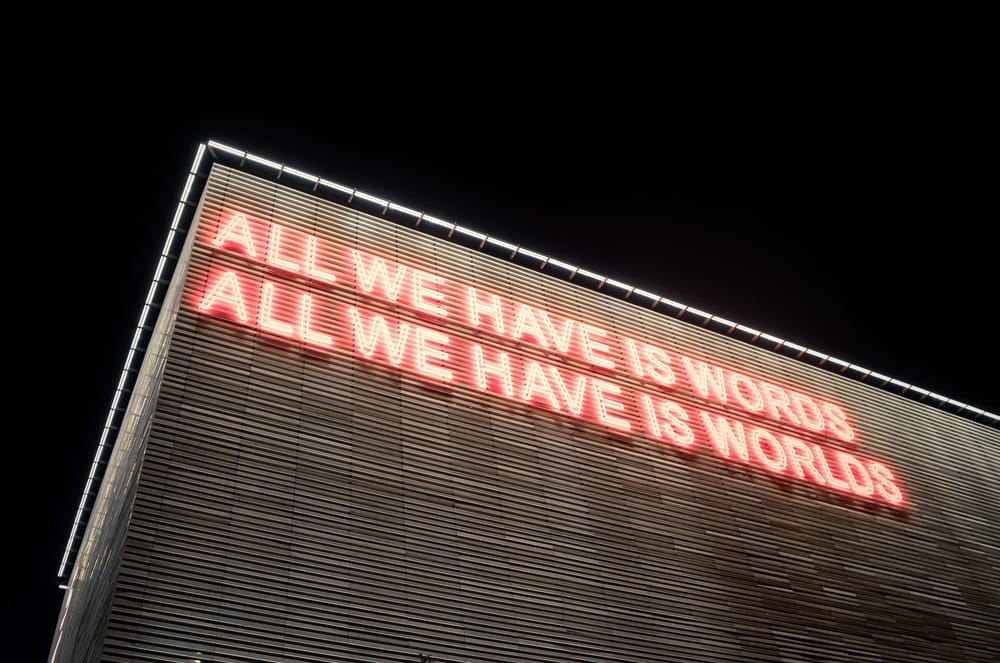

There’s a psychological barrier that divides the world into two distinct camps: those who build things and those who only critique them.

This barrier has nothing to do with technical skill, intelligence, or even opportunity.

It’s the ability to absorb embarrassment.

It’s what we might call "cringe tolerance."

Every entrepreneur, artist, or innovator who has achieved longevity has endured the particular agony of putting imperfect work into the world. They've had to ship products with bugs, publish essays with typos, launch businesses with amateur websites, and present ideas that initially sound absurd.

The difference between builders and non-builders comes down to this: who can stomach the discomfort and who cannot.

The Anatomy of Cringe

Cringe tolerance describes the psychological capacity to act despite the certainty that others will judge your work as amateurish, naive, or embarrassing. It's the ability to post your first YouTube video knowing it will be awkward, to launch a website despite its obvious design flaws, to share your writing before it reaches professional polish.

This tolerance operates on multiple levels - the immediate cringe of putting work out before it's "ready," the sustained cringe of defending something imperfect, and the retrospective cringe of looking back at earlier efforts. Each level requires its own form of psychological fortitude.

Facebook began as a crude Harvard directory with the tagline "A Mark Zuckerberg production." YouTube's first video featured a 19-second clip of someone standing in front of elephants. Twitter launched with the question "What are you doing?" rather than "What's happening?"

These origins were undeniably amateur.

Benjamin Franklin's early attempts at writing were so awkward that his brother James refused to publish them in the New-England Courant. Franklin persisted, eventually developing the pseudonym "Silence Dogood" to get his work published. His initial efforts were undeniably amateur, yet he tolerated the embarrassment of imperfection long enough to develop genuine skill.

Virginia Woolf captured this tension perfectly in her essay "A Room of One's Own," where she described the psychological barriers facing women writers. The fear of appearing foolish, of being judged as presumptuous for attempting serious work, paralyzed many potential creators. Those who succeeded were often those who could tolerate being dismissed as amateurs long enough to develop genuine expertise.

The Perfectionist's Paradox

The cringe-intolerant mind operates under an evolutionarily defensible but fatal assumption: that work should only be shared when it reaches some mythical standard of completeness. This perfectionist impulse feels virtuous in its standards. Why would anyone want to put subpar work into the world?

But this thinking contains a flaw. It assumes that perfection is achievable in isolation, that one can reach professional quality without the messy process of iteration, feedback, and gradual improvement. History suggests otherwise. The Wright brothers' first flight lasted twelve seconds and traveled 120 feet. Shakespeare's early plays were considered crude by contemporary standards. The first iPhone lacked copy-and-paste functionality.

By refusing to tolerate initial embarrassment, you almost guarantee that you will never reach the competence that would eliminate it.

The only path to eventually producing non-cringe is through the temporary production and embrace of cringe.

The Feedback Loop of Creation

Building means entering a feedback loop that inevitably begins with embarrassment. You create something imperfect, share it, receive criticism, improve it, and repeat. This process only works if you can tolerate the initial discomfort of showing incomplete work.

The cringe-intolerant never enter this loop. They polish endlessly in private, seeking some impossible standard of perfection before sharing. Meanwhile, the cringe-tolerant ship early, learn from real-world feedback, and iterate rapidly.

Over time, this difference compounds.

Think about the difference between a novice writer who publishes a weekly blog post despite its obvious flaws and another who spends months perfecting a single essay in private. The blogger will likely produce better work within a year, having learned from reader responses, developed their voice through practice, and built an audience that provides ongoing motivation.

The Social Dimension

Most acts of building require convincing others to take you seriously before you've proven yourself - pitching ideas that sound naive, asking for help when you're clearly inexperienced, and representing projects that are obviously incomplete.

Most founders recall their early pitches as embarrassingly amateur. They mispronounced industry terms, made obviously flawed financial projections, and stumbled through presentations. But they persisted through this discomfort, gradually learning to communicate more effectively.

The alternative approach - waiting until you can pitch perfectly - rarely works. By the time you've achieved that level of polish, the market opportunity has often passed, or your idea has become outdated. The ability to tolerate looking foolish while learning becomes essential for progress.

The Silicon Valley culture of "failing fast" represents an extreme form of cringe tolerance, where embarrassing failures are almost celebrated as learning experiences. It’s a cultural norm that enables rapid experimentation and iteration, even when individual attempts look naive or misguided.

The Compound Effect

The creator who can stomach early embarrassment eventually produces work that is far less embarrassing than someone who has waited for perfection. This happens through multiple mechanisms: practice improves skill, feedback refines judgment, and confidence develops through accumulated experience.

More than that: audiences respond more to authentic imperfection than to sterile perfection. The early, rough attempts connect with actual people, while polished work feels distant or manufactured.

This creates a virtuous cycle: tolerance for imperfection actually leads to better outcomes.

The discomfort of sharing imperfect work is temporary, while the regret of never sharing can be permanent. The embarrassment of a failed project fades quickly, but the pain of unexpressed potential can last for decades.

The advice is straightforward: start before you're ready, share before it's perfect, and embrace the temporary discomfort of appearing amateur.

The alternative - waiting for competence before attempting - guarantees that competence will never arrive.