Why a Maximum Viable Promise Beats an MVP

In 1876, two men raced to the patent office. One was Alexander Graham Bell. The other was Elisha Gray. Both had been working on a "talking telegraph," a device that could transmit speech over wires. Bell filed his patent first. Gray submitted a caveat just hours later. The legal skirmish that followed became one of the most contentious in telecommunications history.

The part that matters: Gray's design may have been more technically sound. Some historians argue he had a clearer understanding of how to transmit vocal frequencies. But Bell had something else - a compelling, consumable vision. He understood not only what the technology could do, but what it meant. While Gray saw a feat of engineering, Bell saw a civilization-changing network. Bell got the backing, the narrative, the press. Gray became a footnote. Bell became a verb.

This is the earliest MVP lesson most people never learn.

You can invent the future and still lose it. And it has nothing to do with whether your product does or doesn’t work. It’s because your promise didn’t land.

William Stanley Jevons was a 19th-century economist and logician who once attempted to create a logical piano - a physical machine that could generate valid syllogisms using levers and keys. It worked. It was real. And nobody cared. The machine delivered flawless logic; but it promised a future no one wanted.

This pattern repeats. Over and over. The product, in its embryonic form, is a placeholder. It stands in for the larger commitment: a story about what will be possible. It is the vessel for the promise.

The MVP, as it’s usually conceived, is framed as a minimum viable product - a trimmed-down prototype that can be tested in the wild. But that phrase is misleading. Products don’t become viable when they meet some technical baseline. They become viable when the promise behind them is credible, desirable, and emotionally resonant enough to create momentum.

What matters is not the prototype. What matters is what it says.

The Maximum Viable Promise

A maximum viable promise is the most ambitious version of the future that a founder can offer, while still being credible. It lives in the uncanny valley between marketing and mythology. It requires a founder to occupy the strange position of both oracle and operator.

The maximum viable promise isn’t a lie. But it is a fiction. A fiction in the James Wood sense: a narrative with internal rules, operating under a suspension of disbelief. The promise is the scaffolding the product will eventually grow into.

There are obvious risks. Theranos was a non-viable promise without a minimum viable product. So was WeWork’s "WeOS." So was the Antikythera mechanism, if you count ancient technology sold to modern archaeologists as myth. These collapsed because they oversold the fiction and underbuilt the system. But the inverse is also common: brilliant engineers with functional products who never articulated a world big enough to attract belief.

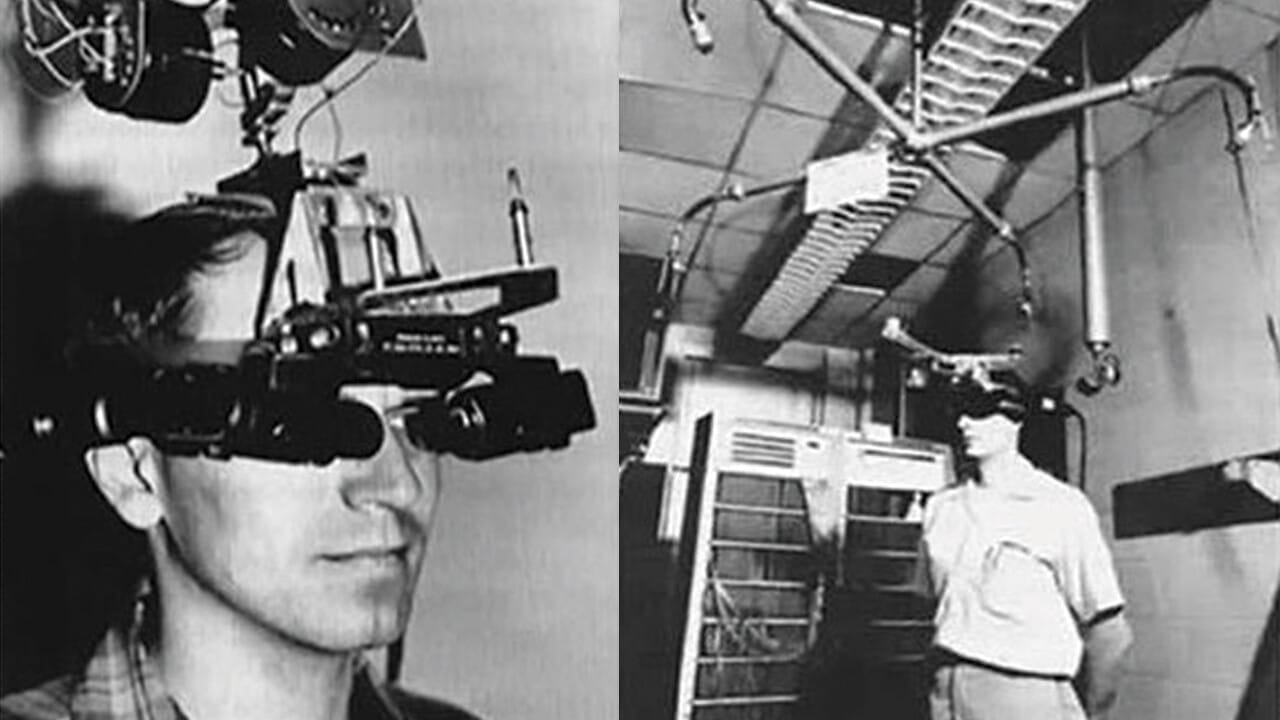

In 1968, Ivan Sutherland created the first head-mounted display system - a precursor to modern AR. It was called the Sword of Damocles, partly because it had to be suspended from the ceiling. Technically, it worked. Culturally, it failed. No one knew what to do with it. It lacked a narrative container.

Founders are taught to build the thing and let the results speak for themselves. But this assumes the world is already listening. Most of the time, it isn’t.

Narrative as Infrastructure

During the Apollo program, NASA had the technology to land a man on the moon. But they also needed to construct a narrative framework to justify the cost, coordinate the institutions, and sustain public will. Kennedy’s 1962 Rice University speech was political rhetoric; but it was also an eternally echoing, maximum viable promise.

"We choose to go to the Moon... not because it is easy, but because it is hard."

The real work happened in labs and factories and behind desks. But the speech was necessary to make the work legible, to enroll millions of people in a shared vision of the future. Narrative, in this sense, is not decoration. It is infrastructure.

Founders build narrative infrastructure when they say, "We're going to make the internet programmable." Or "We're going to bring money online." Or "We're going to make every company an AI company."

Or when they are as audacious as Charles Fourier, who promised in the 19th century that his phalanstères would reorganize society, eliminate poverty, and harmonize human passions. Fourier never built a functioning commune, but his vision was contagious enough to inspire dozens of attempts across the US and Europe. The product was never there. The promise was the whole show.

The value of these claims is not in their immediate verifiability. It's in their catalytic function. They make people care.

The Delta is the Asset

When a startup raises capital, it does so not on what it has, but on what it might become. The difference between where the company is and where the story says it will be - that gap is the delta. And the delta is what gets funded.

A startup with a good product and a bad story has trouble raising. A startup with a credible story and a weak product often gets the runway to fix it. This is frustrating to technical founders who want to be rewarded for execution. But venture capital is a derivatives game. Investors are buying exposure to optionality.

You sell the dream. You ship the excuse. You raise on the delta.

This doesn’t mean lying. It means understanding what your story unlocks. It means being precise about the shape of the future you claim, and persuasive in your claim to own it. The delta is an asset if you know how to manage it.

It helps to remember that Ada Lovelace predicted general-purpose computing a hundred years before it was viable. Her “Analytical Engine” was never built in her lifetime. But her notes were a blueprint for what the machine meant, not just what it did. She sold the promise. The world eventually caught up.

Why the MVP Model Fails Founders

The MVP model, taken literally, misleads founders into building too conservatively. They sand off ambition in the name of iteration. They ship prematurely, afraid of overpromising. They test things so small they never create gravity.

But customers and investors don’t react to products in isolation. They react to context. To positioning. To the signal a product sends about the person or team behind it.

A small product with a big narrative earns a second look. A small product with a small narrative gets forgotten. The MVP approach, when followed dogmatically, encourages the latter.

Paul Graham once noted that the best startup ideas often look like bad ideas at first. He didn’t say they sound like bad ideas. Founders often conflate the two. But a good idea that sounds good will always outperform a good idea that sounds dull.

Sounding good is narrative work.

Selling the Dream, Surviving the Real

There is a temptation to divide the founder journey into two phases: storytelling, then execution. But these are not sequential. They are parallel, interleaved, recursive.

Promising something ambitious forces you to grow into it. Promising something safe tempts you to coast.

To promise well is to obligate yourself to rise. To put a reputation on the line. To make a public bet with the future. This is why the best promises feel slightly too large. They contain the risk that you might be wrong, and the humility to admit you aren’t there yet.

But if they’re viable - if they reflect something you truly believe you can earn - they are also magnetic.

The founder becomes the focal point of a new gravitational center. Employees orbit. Investors orbit. Customers orbit. Not around the current product, but around the future that product gestures toward.

That’s what the MVP should mean.

The Role of Language in Early-Stage Success

In The Rhetoric of Reaction, Albert Hirschman described three common arguments used to resist progress: perversity, futility, and jeopardy. Founders hear all three.

"If this worked, someone else would have done it already." "Even if it works, it won’t matter." "Trying it will only make things worse."

To overcome these requires more than engineering. It requires rhetoric.

Founders often underinvest in language. They hire a copywriter late. They treat marketing as polish. They don't realize that early-stage success is often a language problem. Can you explain what you're building in a way that makes people want it to exist? Can you tell a story that makes the future feel inevitable?

Steve Jobs was a technologist. But he was also a rhetorician. He made people want things they didn’t know they needed. He made the story feel personal. That ability mattered just as much as the design.

To make a maximum viable promise is to make a kind of vow. You say: I will build this, or I will die trying. Not in some theatrical sense, but in the sense that your credibility and effort become inextricably linked to the claim.

You sell the dream. You ship the excuse. You raise on the delta.

But if the promise is authentic - if it emerges from something you feel must exist - then the dream sells you, too. It demands more than iteration. It demands transformation.

The MVP was never the prototype. It was the provocation.

The product comes later.

As proof you meant it.