Why Intelligence Is a Terrible Proxy for Wisdom

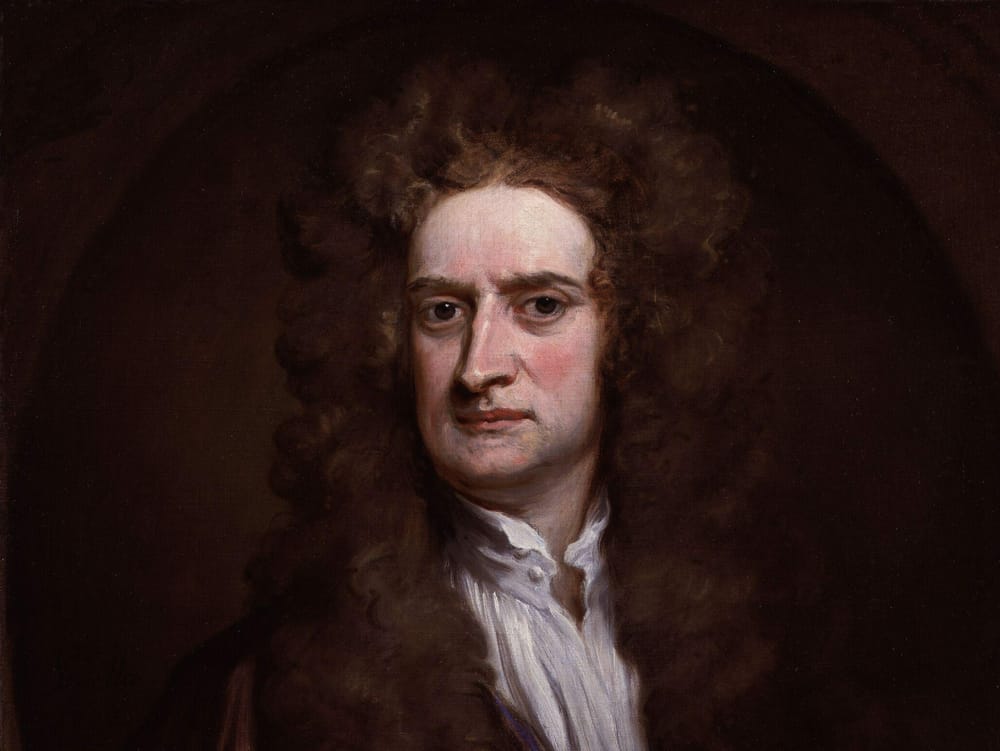

Isaac Newton, one of the greatest scientific minds in human history, lost a fortune in the South Sea Bubble of 1720.

After initially making money and selling his shares, he bought back in at the peak, watching helplessly as the stock collapsed. His reported loss was around £20,000, equivalent to several million dollars today. Newton invented calculus and described the laws governing planetary motion, but he couldn’t resist a speculative mania that, in retrospect, had all the hallmarks of obvious fraud. “I can calculate the movement of stars,” Newton allegedly said, “but not the madness of men.”

In the 2020’s, Newton might have been all-in on Crypto...

Linus Pauling won two Nobel Prizes, one in Chemistry and one in Peace, making him one of only five people to win the Peace Prize twice. And he spent the last decades of his life promoting megadose vitamin C as a cure for the common cold and, eventually, cancer, based on theories that never held up to rigorous testing. Bobby Fischer, the greatest chess player who ever lived, descended into paranoid antisemitic conspiracy theories after his world championship victory. John von Neumann, the polymath who contributed to quantum mechanics, game theory, computer science, and economics, was reportedly a terrible driver who wrecked cars with alarming frequency despite being able to perform complex calculations in his head.

Sometimes, brilliant people end up spectacularly, catastrophically wrong in ways that ordinary people avoid.

Because sometimes, brilliant people have extraordinary blind spots.

And, every now and then, a brilliant person can be a complete fool.

Popular belief (and hoards of Elon Musk fans on Twitter) holds that smart individuals - the geniuses we laud - should make fewer errors across all domains. If you have more processing power and superior reasoning abilities, surely you’ll arrive at correct conclusions more often than someone without those gifts.

But this model treats the brain like a calculator that either works well or poorly, when it’s actually more like a lawyer: capable of arguing any position with varying degrees of skill. Give a mediocre lawyer a bad case, and there is a better-than-not likelihood they’ll lose. Give a brilliant lawyer a bad case, and they’ll construct an elaborate, internally consistent, superficially compelling argument for why they should win anyway. See: Boston Legal.

Intelligence doesn’t merely help you find truth. It helps you construct persuasive narratives. And the person most easily persuaded by your narratives is yourself.

Francis Bacon identified this problem four centuries ago, writing about the “idols of the mind” that distort human reasoning. The intelligent person excels at building coherent worldviews and defending positions against attack. These are precisely the skills that make motivated reasoning so dangerous when they’re turned inward.

Simply put: smart people, by virtue of being very fucking smart, are better at constructing post-hoc rationalizations for beliefs they hold for emotional or social reasons. Everyone does this to some extent. We form impressions and then search for evidence to support them. But intelligent people search more effectively. They find better evidence, or at least better-sounding evidence. They anticipate counterarguments and preemptively defuse them. They build fortresses of logic around conclusions they reached for entirely non-logical reasons, and those fortresses can become so elaborate and well-defended that the person living inside them never realizes they’re trapped.

Philip Tetlock’s research on expert political judgment found that the experts with the most impressive credentials and the strongest reputations for insight performed barely better than chance at predicting geopolitical events, and sometimes performed worse than simple algorithms. The experts who performed best tended to be what Tetlock called “foxes” rather than “hedgehogs,” borrowing from Archilochus’s ancient distinction. Hedgehogs know one big thing and apply it everywhere, while foxes know many small things and adapt flexibly. The hedgehogs were frequently the most intelligent and articulate members of the sample. They also consistently overestimated their own accuracy and failed to update their beliefs when predictions went wrong.

Intelligence, it seems, can produce a particularly fraught form of intellectual pride. You’ve been right so many times before, in so many situations, in ways that others couldn’t match.

Milton’s Satan in Paradise Lost is brilliant and utterly self-deceived, constructing an entire theology to justify his rebellion while remaining blind to his own vanity. Dostoevsky’s Underground Man is excruciatingly self-aware and analytically sophisticated, using that sophistication primarily to torture himself and others while accomplishing nothing. Faust trades his soul for knowledge, only to find that knowledge without wisdom leads to destruction.

Why?

- First, there’s the tendency to mistake complexity for correctness. Simple explanations feel too simple for someone who can handle complexity, so they reach for more elaborate theories even when Occam’s razor should apply.

- Second, the ability to construct unfalsifiable frameworks that explain everything while predicting nothing, intellectual houses of cards that look impressive from the outside but contain no load-bearing walls.

- Third, the social reinforcement that comes from being consistently regarded as the smartest person in the room, which makes it harder to accept that someone with less raw intelligence might be right when you’re wrong.

- And fourth, the way that verbal facility can substitute for actual understanding, allowing someone to explain something convincingly without genuinely comprehending it themselves.

Wisdom is knowing what you don’t know.

Wisdom is what tells you to ignore the memecoin // prediction market bet, even though you could construct an excellent narrative explaining why this time will be different. Wisdom is what tells you that your political opponents might have a point, even though you could demolish their arguments in debate. Wisdom is what tells you not to install Clawdbot on your personal device and give it access to your banking details, even though you could become the next Tony Stark.

Intelligence can be measured on tests.

Wisdom is a good deal harder to quantify.

Isaac Newton never figured out the madness of men. He also never figured out alchemy, which consumed years of his life in fruitless experimentation. The mind that revolutionized physics believed he could transmute base metals into gold. That should tell us something. Our greatest strengths can coexist quite comfortably with our most embarrassing weaknesses and our worst impulses. The smartest person you know is probably an idiot in some domain that matters. If you’re the smartest person you know, the domain that matters might be closer than you realize.