How Convenience Kills Curiosity

I’ve been thinking about the death of curiosity.

Remember when you had to figure out how a new piece of software worked by poking around its menus?

When finding an obscure fact meant wandering through library stacks, accidentally discovering three unrelated interesting things along the way?

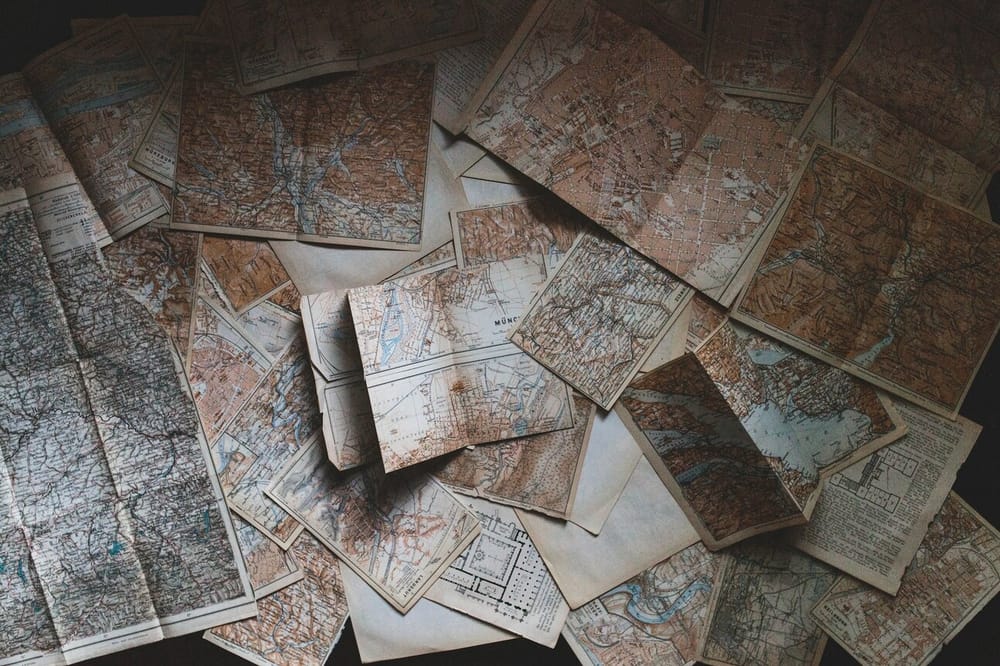

When getting somewhere required unfolding a paper map so massive it would never fold back correctly?

Those friction-filled experiences are nearly extinct now. We’ve optimized them away in the name of convenience, and something important has been lost in the transition.

Type a question, get an answer—ideally without even clicking through to a webpage. The algorithm tries to anticipate exactly what you want, then delivers it with surgical precision. This seems like an unalloyed good until you realize what’s missing: the pathway of discovery, the intellectual side-quests, the context that situates knowledge within a broader landscape.

Every product manager in Silicon Valley has been trained to reduce friction. If it takes three clicks, reduce it to two. If it takes two, try one. If users have to think, it’s considered a failure. The ideal interface is intuitive, immediate, invisible. And it works—until it works too well.

Because in the real world, knowledge is earned through movement. Friction. Ambiguity. The old experience of falling into a stack of books at the library wasn’t efficient, but that was hardly the point. You’d go in looking for one answer and come out with five better questions. That’s how curiosity thrives: in the space between expected and unexpected, between map and territory.

UX optimization reorients the human toward delivery over discovery. You’re no longer hunting; you’re being served. Platforms track your behavior and give you more of what you already like. Spotify doesn’t ask you to browse—it predicts your vibe. It’s all so thoughtful, so personalized, so utterly numbing. When systems get good enough at anticipating your preferences, your preferences shrink. The feedback loop closes. Curiosity flattens.

There’s a concept in behavioral science called the “effort heuristic.” It’s the idea that we tend to value information more if we worked for it. The more effort something requires, the more meaning we assign to the result. When all knowledge is made effortless, it’s treated as disposable. There’s no awe, no investment, no delight in the unexpected—only consumption.

Convenience rewires the mind. It makes learning feel like confirmation. It reduces exploration to retrieval. You end up knowing more but noticing less.

It’s not that user experience designers are trying to kill curiosity. They’re trying to help. But help, at scale, becomes architecture. And architecture shapes cognition. The interfaces we use become metaphors for how we think the world works. If your phone always gives you the answer, you stop asking better questions.

We don’t need more information. We have oceans of it. What we need are tools that reintroduce friction in thoughtful ways. Interfaces that don’t just answer us, but provoke us. Not to make things harder for the sake of it— to remind us that adult curiosity is not a default state. It must be cultivated. And right now, the culture of convenience is starving it.