A Metabolic Workspace

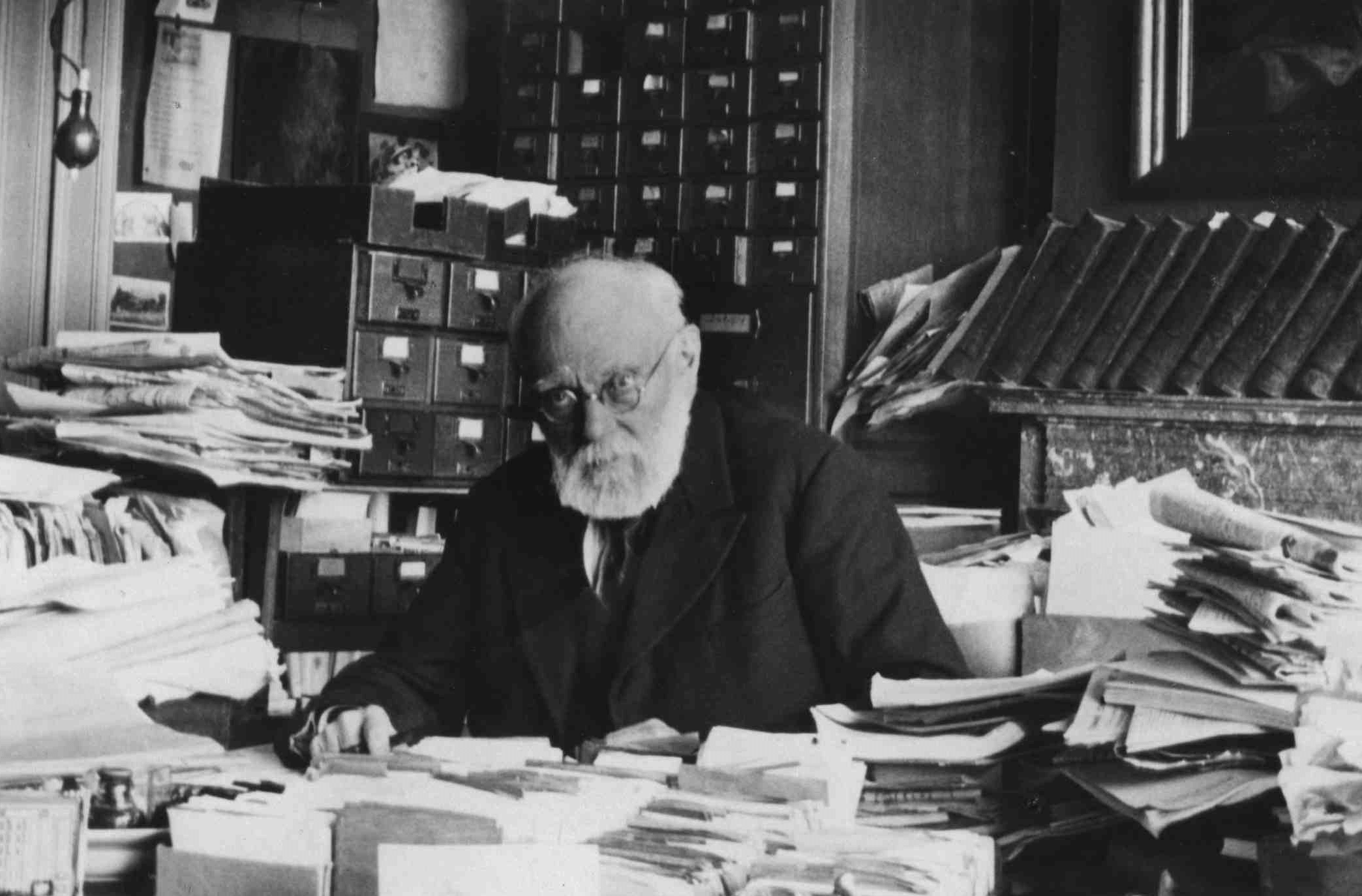

In 1895, a Belgian lawyer, bibliographer and information scientist named Paul Otlet started building what he would call the Mundaneum: a vast repository in Brussels containing over 12 million index cards cross-referenced by subject, designed to hold the entirety of human knowledge. Otlet had already predicted hyperlinks, search engines, and something resembling the internet decades before ARPANET. He believed that if humanity could only organize all its information properly, world peace would follow.

The Nazis (of course) destroyed most of it in 1940 when they needed the space for a Third Reich art exhibition. The surviving fragments sit in a museum now, a remnant of the dream that perfect information storage would save us...

The productivity internet has spent the last decade keeping that dream alive by building elaborate Second Brains, and as far as I'm concerned, as far as many of my fellow aspirants are concerned, the results are in. Most of these systems become digital landfills within months. The average Notion user creates dozens of databases they'll never touch again. And anyone who's been in the productivity space long enough has noticed the pattern: the people writing the most about note-taking systems seem to produce the least actual work.

I was one of 'em.

For years, I built elaborate capture systems, tagged everything meticulously, created bidirectional links between concepts like I was weaving some grand intellectual tapestry. And at some point I noticed that my output had actually decreased. I was spending more time organizing thoughts than having them.

Well, I burned it all down; and I've started experimenting with something different.

So: Digestion

I call it (for now) the Metabolic Workspace, and the idea is to try to invert the premise of personal knowledge management.

It's very much a work in progress, but the core idea is simple: information should be treated like food, not furniture. I don't keep every meal I've ever eaten stored in my basement. That's a disgusting notion. I eat, extract the nutrients, and let the rest go. Ideas have a half-life, and clinging to them past their expiration date actually poisons my ability to think clearly.

Unlike a Second Brain - which functions as a storage unit - the Metabolic Workspace functions as a digestive system. It assumes that information has nutritional value that expires. If I don't use the idea, it becomes waste and must be expelled to keep my actual brain healthy.

The concrete implementation looks like this so far: no inbox, no "read later" list, no archive folder. Everything goes into a single daily note. Ideas can only enter the system if I translate them into my own words from memory.

Funes and His Perfect Memory

Jorge Luis Borges wrote a short story in 1942 called "Funes the Memorious" about a young man who, after a horseback riding accident, develops the ability to remember everything perfectly. Every leaf he's ever seen, every word of every conversation etc etc. Funes can no longer generalize or abstract. He's bothered that the word "dog" applies to both the dog he viewed from the side and the same dog viewed from the front. Overwhelmed by infinite perfect detail, Funes lies in a dark room, unable to sleep, unable to forget, essentially paralyzed.

Borges was writing about something specific here. Funes can perceive but cannot think. "To think is to forget a difference, to generalize, to abstract," Borges writes. "In the overly replete world of Funes there were nothing but details."

I wonder if a good many productivity hoarders have replicated Funes's condition at the system level. When you can instantly retrieve that interesting article about circadian rhythms you bookmarked in 2019, you feel like you're thinking. But are you? Or are you just Ctrl+F-ing through an ever-expanding archive of other people's thoughts, too full of details to synthesize anything new?

In fairness to the collectors: there's a venerable tradition of treating knowledge accumulation as sacred work. Medieval monks spent entire lifetimes hand-copying manuscripts, and we're lucky they did. The only reason we can read Lucretius or Catullus today is because some anonymous Carolingian scribe thought their words worth preserving. If those monks had adopted a weekly cremation protocol for their scriptoriums, we'd have lost most of classical literature.

Frances Yates, in her landmark 1966 study "The Art of Memory," documented how ancient and medieval thinkers used elaborate mental architectures to store vast quantities of information. Greek and Roman orators constructed imaginary palaces in their minds, placing speeches and arguments in different rooms, then "walking" through the palace during performances. The technique traces back to the Greek poet Simonides, who discovered the method after a roof collapse killed his fellow banquet guests - he found he could identify the crushed bodies by remembering where each person had been sitting. The Romans inherited and refined these techniques, and in the medieval period, trained memory became linked to the cardinal virtue of Prudence. Before the printing press, the capacity to retain and retrieve information was considered a fundamental intellectual skill.

So who's right?

I think the answer depends on what you're actually trying to do with all of this information - all of this ephemera - all of this stuff.

Two Completely Different Activities Wearing the Same Hat

When the monks copied Virgil, they were engaged in cultural preservation. The goal was transmission across time. Any individual monk's personal relationship to the Aeneid was incidental to the project of ensuring future generations could access it.

When you highlight an article about circadian rhythms, what exactly are you doing? If you're a sleep researcher building a literature review, you're engaged in something like scholarly preservation, and robust archival systems make sense. But most of us aren't sleep researchers. Most of us highlighted that article because it was mildly interesting on a Tuesday afternoon and we vaguely imagined our future selves might want it.

Uncomfortable: how often has your meticulously organized Second Brain actually produced something that couldn't have been created with a simple web search at the moment of need?

I've asked this question to dozens of personal knowledge management enthusiasts, and the answers are consistently awkward. There's usually a long pause followed by a single example from three years ago, described in enough detail that I suspect it's the only example.

There is a rude but clarifying question here: are you collecting information to use it, or are you collecting information because collecting feels like intellectual work? If it's the latter, you're not building a Second Brain; you're building an anxiety management system that happens to look like productivity.

Six Ideas

I've started experimenting with a few interconnected principles for a metabolic workspace. Each one (ideally) reinforces the others.

The Single-In Protocol forbids me from having an inbox, a "read later" list, or a notes folder. I have one single note, separated by date headers. Every thought, quote, or task from each day goes there. Ideally, prevents the fragmentation of self, where ideas hide in nested folders I'll never open.

Echo-Only Capture means I can't clip articles or copy-paste long passages. To enter the system, an idea must be translated. I read the text, close the source, and write what remains in my own voice. If I can't remember it well enough to summarize it, it hasn't been digested yet and doesn't deserve a place in my workspace.

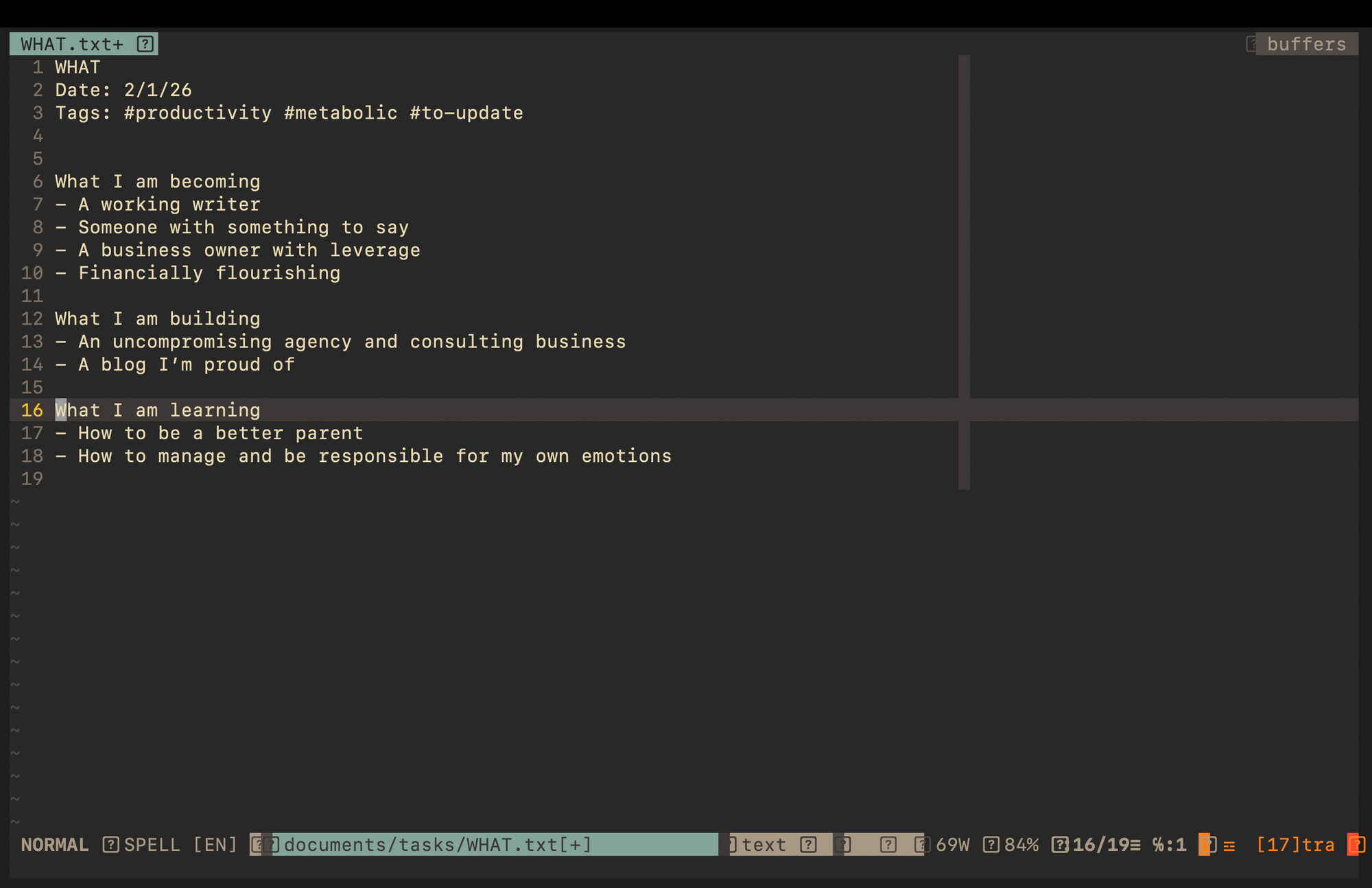

The WHAT Anchor sits pinned at the top of my app. It contains only three headers: What I am becoming (a high-level personal evolution goal), What I am building (the current project), and What I am learning (the single topic of current curiosity).

The Weekly Extraction happens every Sunday. I read through my daily notes, copy the nutrients (the one or two sentences that actually changed my thinking), and add them to either my WHAT note, or a dedicated note if it's important enough to keep.

For dedicated notes, Agency-Tagging replaces noun-tags like #philosophy or #marketing with action-verbs. I tag a note by how I'll use it: #To-Argue, #To-Experiment, #To-Teach, #To-Embody. This transforms a static archive into a dynamic to-do list of thoughts.

Somatic Metadata links digital files to embodied memory. Every input must include a brief description of the feeling that prompted it. "Note taken while feeling restless in a cafe." "Written with a sense of urgency after the meeting." This makes it easier for my brain to recall the context.

My Weekly Extraction Ritual

I open my WHAT note and my daily note file. For each daily note, I ask:

- Did anything here change how I think about my three WHATs?

- Is there a single sentence, note or idea worth preserving in my active system?

- Has this thought already become part of how I see the world?

If yes to the first two, I copy that sentence (just the sentence) to my WHAT note under the relevant header, or I create a dedicated note.

If yes to the third, the insight has already been metabolized and I can move on.

A Crucial Distinction: Your Thoughts vs. Other People's Thoughts

The whole argument against hoarding is about other people's thoughts - clipped articles, highlighted passages, bookmarked threads. That's the Funes problem: drowning in details you didn't generate, couldn't synthesize, and won't use.

I want metabolic notes to be different: the output of processing, not raw input waiting to be processed. When you write in your own words what you're thinking about a project, a conversation, a problem - that's you doing the metabolic work the system is designed to encourage.

Why Somatic?

Memory research has consistently shown that recall is heavily context-dependent. The phenomenon called state-dependent learning = information encoded in one physical or emotional state becomes more accessible when you return to that state. Divers who learned word lists underwater remembered them better underwater. People who learned material while sad recalled it better when sad again. Which is why my best work happens while listening to Tom Waits.

Your Second Brain has little somatic metadata. It's disembodied text floating in a void, stripped of the rich contextual markers that would actually help you remember and use it. When you try to retrieve something from your Obsidian vault, you're searching keywords. When you try to retrieve something from your actual brain, you might think "that thing I was reading when I was annoyed at that airport" and the whole cluster of associated memories lights up.

We've been treating digital notes like they're interchangeable with mental notes, when they're actually a much degraded format.

The Trust Problem

The deepest objection I anticipate and have experienced myself: people don't trust their future selves to recreate what they're deleting. What if I need that insight about circadian rhythms in five years? What if the perfect sentence comes to me while walking and I delete it before I've found a project for it?

This fear is understandable; but it’s a fear that assumes ideas exist independently of the person who has them. That an insight is a discrete object that can be lost, like a set of keys. The Metabolic concept rejects this entirely. If an idea was truly important, it has already changed your thinking. The note is documentation of a transformation that has already occurred. Deleting the note doesn't reverse the transformation.

This matches my actual experience with creative work. The best ideas I've ever had don't live in any note-taking system. They're part of how I see the world now. I couldn't forget them if I tried. The ideas I've carefully preserved in digital archives, by contrast, mostly feel like strangers when I rediscover them. "Did I really think this was important?"

The answer is usually: yes, for about a week.

How to Start Today

If this interests you, give it a try. Remember: it's an imperfect system, and if you have ideas for me, or if you find it either useful or useless, reach out.

- Step 1: Start Again Create an entirely new folder, or a new graph, or a new instance of whatever note taking or text editing tool you're using.

- Step 2: Create Your WHAT Note Open your notes app. Create one note called WHAT. Add three headers: What I am becoming. What I am building. What I am learning. Fill in one answer for each. This is now the sun your system orbits.

- Step 3: Start Your Daily Note Tomorrow morning, create a note called The Daily and add a header for the date. Everything goes here. Every thought, task, quote, idea. One note. One day.

- Step 4: Apply Echo-Only The next time you want to save something from the internet, close the tab first. Write what you remember in your own words. If you can't remember enough to write anything useful, you've just learned it wasn't worth saving.

Alternatively: take any of these ideas that appeal to you and discard the rest. Don't feel confined to a system. Be a magpie.

Synthesis + Discomfort

I don't think the Metabolic Workspace is right for everyone. And I'm still uncovering flaws as I'm building it out. There are genuine use cases for long-term information storage, particularly in professional and academic contexts where you're building on a literature over years.

But I think we've conflated two very different activities: thinking and documenting thought. We've assumed that building the perfect documentation system would automatically improve our thinking. And we've spent a decade discovering that this assumption was backwards.

The person who reads a book, thinks hard about it, discusses it with friends, and then forgets most of the details has genuinely engaged with ideas. The person who highlights the same book, exports their highlights to Readwise, auto-syncs them to Notion, and never looks at them again has performed the ritual motions of intellectual work without the substance. One of these folks will grow. The other will grow their database...

Paul Otlet's work didn't bring about world peace. But even if the Nazis hadn't destroyed it, even if the 12 million index cards had survived and grown to 120 million, I doubt the outcome would have been different. The bottleneck on human wisdom was never storage capacity. It was always something harder to engineer: the willingness to actually think.